Enjoy browsing, but unless otherwise noted, these houses are private property and closed to the public.

So don't go tromping around uninvited! CTRL-F to search within the page.

THE 1958 ARTHUR CONNELL HOUSE HISTORY

1170 Signal Hill Road, Pebble Beach, Monterey County CA.

Report commissioned by site owner, Massy Medhipour, as part of an agreement with Monterey County. Written by Erica Schultz and Sheila McElroy.

Introduction

By the time that Richard Neutra received the commission to design Arthur Connell’s house in the late 1950’s he had three decades of connections with the intellectual life of the Monterey Peninsula. The connection started with a lecture in the fall of 1928. It continued with his early and continuing support of the careers of Edward and Brett Weston and with architectural assignments in the Monterey area in the late thirties and early forties and his ongoing relationship with Monterey-area media personality John Nesbitt. So he came to the Connell commission with a familiarity and deep appreciation of the cultural and natural assets of the area.

It is a mistake to characterize the Connell house in Pebble Beach as a foreign “international style” created by an outsider. It is true that the Connell House’s flat roof, unornamented white surfaces and extensive use of glass would match the criteria laid down by Hitchcock and Johnson to qualify as “International Style,” (Hitchcock HR and Johnson P, The International Style, WW Norton, New York 1932). However, the separation of vertical and horizontal planes, “exploding the box,” descends from Neutra’s idol, Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1909 Gale House.

Significance

Completed in 1958, the Arthur and Kathleen Connell House was an excellent example of the International Style within the Modern Movement in Pebble Beach, California, and it was representative of master architect Richard Neutra’s midcentury residential work. The house exemplified the rational design approach associated with Modem architecture, with thoughtful delineations between public and private areas that did not compromise its open, flowing spatial quality. (1)

With its complex but controlled massing, the Connell House embodied Neutra’s grand dual concern to design the house to meet the family’s needs and also to exploit the meeting of land and water below. In this regard he succeeded admirably, with every room, save the private den, commanding a stunning view of land and sea from Cypress Point northward.

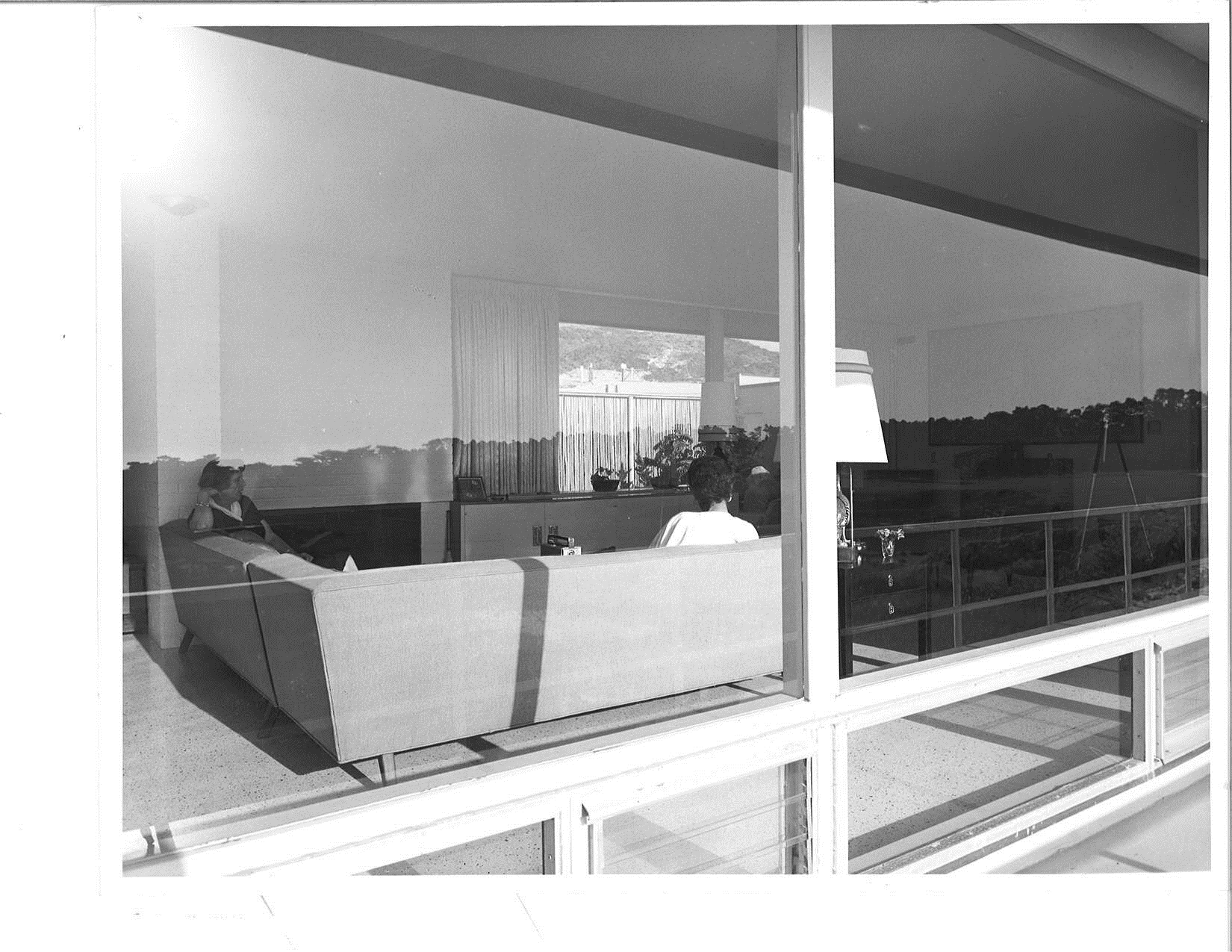

The property was one of thirteen of Neutra’s twenty extant northern California projects retaining integrity. (2) Within that small number, a fraction of Neutra’s canon, the property stands out for its stunning response to program and site. Lying long and low, hugging the earth, open to light and nature, the Connell house exhibited those signature elements associated with Neutra’s residential architecture of the 1950s, including cantilevered roof slabs, crisp geometries, projecting beams, ribbon windows, and glass walls, culminating in what his biographer Thomas Hines identified as the most essential character of his work, “the interpenetration of inner and outer space.” (3)

Description

The single-family residence at 1170 Signal Hill Road was completed in 1958 and later enlarged by construction of an addition at the southwest corner of the upper level. It was set into a slope on the west side of Signal Hill Road, a short, winding, street that extends steeply uphill from 17 Mile Drive. The house was set high above the Pacific Ocean, between Cypress Point Golf Course and Spyglass Hill Golf Course, in Pebble Beach. This unincorporated area of the Monterey Peninsula is also known as Del Monte Forest. The 2.13-acre parcel on which it was located is graded for a short distance to the west, then sweeps downhill. It was landscaped with a scattering of cypress trees to the north and east, some of which were planted by the original owners, Arthur and Kathleen Connell, for greater privacy.

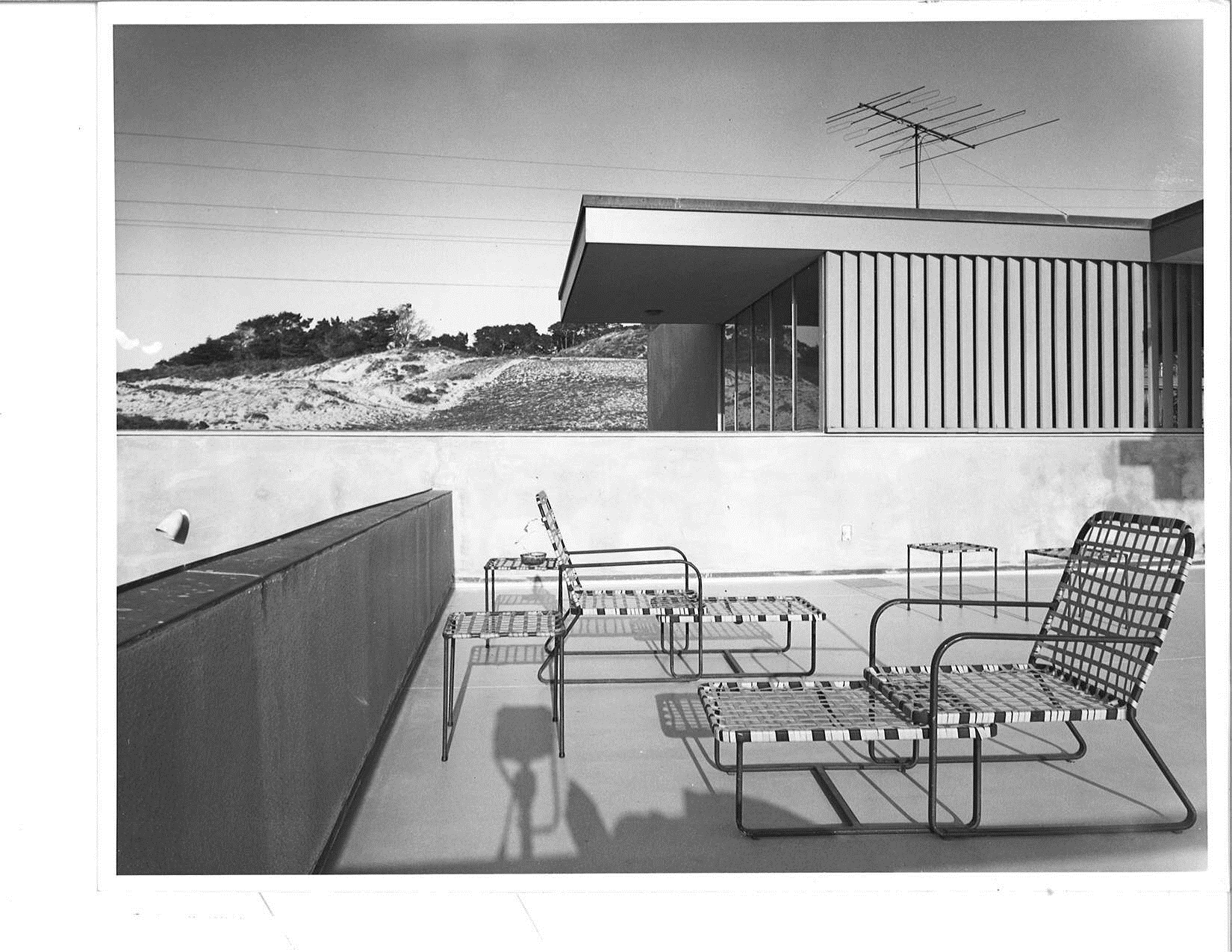

The house was designed for the Connell family by master architect Richard J. Neutra, who conceived of it as a long, low arrangement of orthogonal volumes and planes with dramatic views of land and sea. The upper level was U-shaped in plan, organized around a central courtyard that was enclosed on the east side by a tall grape-stake fence. The smaller lower level, beneath the base of the U, was rectangular in plan. The house rested partly on a concrete perimeter foundation and partly on a concrete slab foundation. The unornamented stucco-clad walls were painted a range of soft tones of grey, olive, green, and white. Other contrasting materials added texture and visual interest. These materials include narrow tongue-and-groove siding, painted a flat gray, which formed the cladding on most of the south side, including three swing-up overhead garage doors. Masonite panels, also painted a flat gray, were set below two banks of windows. One bank extended along the west side of the lower level and wrapped the comer to the north side. The other ran along part of the east side of the upper floor, facing the courtyard. The flat slab roof was characterized by wide eave overhangs and broad fascia and was finished with tar-and-gravel. At the northwest corner of both levels, outrigger beams extended several feet beyond the building envelope.

The primary entrance to the house was on the north elevation, at the end of a concrete walk reached by stairs descending from Signal Hill Road. A tall double wood door was flanked on the west by a panel that, like the door, was faced with plywood mahogany veneer. It opens to a half-floor landing illuminated by a band of clerestory windows that wraped around to the west elevation, where angled wooden louvers shielded the landing from the afternoon sun. The entry porch was enclosed by a railing and sheltered by a dramatic projection of the roof slab. A secondary entrance, with an exposed-aggregate concrete floor and a flush door, was located at the southwestern corner of the house, facing east, at the end of an asphalt driveway, where the western part of the building envelope projected some five feet past the garage doors.

Fenestration consisted chiefly of long bands of windows, comprising both floor-to-ceiling glass walls and various combinations of large wood-frame single-light fixed windows and small aluminum-sash casement and double-hung windows. On the upper floor, a window wall ran along part of the west elevation and wrapped around to the north side, flooding the living and dining rooms with light and providing wonderful views of the coastline and the Pacific Ocean. The window wall was composed of six sections on the west side, each featuring a large sheet of plate glass set in aluminum channels and separated by a wood glazing bar from a long horizontal fixed-light window and a small jalousie window below. A shorter glass wall, with large fixed sheets separated by louvered windows, ran along the north side of the courtyard and wraps around the east end of the wing. Two fixed windows on the north side of the lower floor provided natural illumination to the master bedroom. On the west, sliding glass doors opened from two of the three bedrooms to a concrete patio.

Above the ground floor, a cantilevered balcony with a metal railing was shaded by the deep roof overhang and wrapped around the corner to become a large private deck on the north side. The deck was accessed by a massive sliding glass door that was integral with the second-story window wall. On the south side of the north wing, at the top of the broad staircase leading from the half-floor entry hall, a sliding glass door opened to a glazed-tile terrace extending along the west side of the courtyard, which faced an ornamental garden enclosed by a grapestake fence. The roof slab reached several feet over the courtyard on the west and north sides and projected more than six feet on the east end of the north wing, resting on a wooden brace set against the fence. A second sliding glass door opeed to the terrace from the west side of the courtyard. At the northwest corner of the courtyard, a large brick grill for cooking was integral with the interior fireplace in the living room.

1 The significance statement, physical description, and history of the Connell House have been excerpted from Anthony Kirk and Barbara Lamprecht, Arthur and Kathleen Connell House, 1170 Signal Hill Road, Pebble Beach/Del Monte Forest, Monterey County, California, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, January 15, 2014. The excerpted text with accompanying footnotes has been lightly edited for the purposes of this HABS Documentation of the house.

2 Survey of northern Californian properties by Miltiades Mandros, 2003. Barbara Lamprecht Collection.

3 Thomas S. Hines, Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture, 4th ed. (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2005), 14.

Background

Based on archival letters and correspondence, the Connells first became aware of Richard Neutra while living in San Marino, a small Southern California city south of Pasadena, where Arthur Connell, a professional photographer, owned a camera store. While there is no known correspondence in the Connell House file at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) prior to April 25, 1957, his daughter Alexandra Connell recounted her father’s strong sense of aesthetics based on his many activities in photography, the arts, and architecture, leading to his strong admiration for Neutra’s work. Though by the 1950s Neutra was internationally famous, the Connells decided to approach him, initially visiting his Silverlake home and practice.

Neutra was immersed in one of the most productive periods of his career, designing twenty-seven built projects between 1957, when the Connells contacted him, and 1958, when the family moved in. The single-family suburban dwellings designed during this period became known as Neutra’s “Golden Era” of house design. Often naturally finished wood post-and-beam, these houses were more relaxed than his earlier work, characterized as a series of planes set into their surroundings in contrast to his earlier white interlocking volumes of the 1930s.

The Connells purchased the Pebble Beach lot for $13,000. Their primary goal was to create a home that was so fitted to its sloping site that it almost disappeared into the land. In part, this objective also reflected a desire to have a minimum impact on the site, as Alexandra Connell noted. (4) During this time Arthur Connell co-founded Friends of Photography with photographers Brett Weston (Edward Weston’s son), Imogen Cunningham, and Ansel Adams, with whom Connell had taken master classes. Connell and Weston were close friends, often photographing and camping together, deepening the Connell family’s deep affection for the rugged topography and seascape of Carmel and Monterey.

Overlooking the Pacific Ocean and surrounded by two signature golf courses, the Connell House occupied a commanding site in Pebble Beach, Monterey County, lying near the historic 17 Mile Drive and facing the rugged Cypress Point and the ocean.6 Within the canon of Neutra’s deluxe upscale dwellings, only a handful have enjoyed such sites so privileged in striking natural terrain. (7) Here, the dwelling's Pebble Beach setting, with its dunes and wind-pruned trees, was a perfect fit for Neutra, whose background in landscape architecture sharpened his appreciation for special sites.

One of the chief tenets of Modernism is the Wrightian “breaking” of the boundary between indoors and out. In all of Neutra’s work the role of the site and the setting was paramount. Neutra invariably intended to enhance qualities of human well-being by designing houses that melded with nature and the landscape. In many of his single-family free-standing houses including the Connell House, he incorporated the experience of nature at a variety of scales—nature near, nature.at mid-range, and nature distant—to animate interaction with the outdoors. Here, the Connell house itself was an important part, and only one part, of a larger composition.

Neutra’s first gesture was to orient the house to face the spectacular view to the west. A garden courtyard, forming the hollow of the U-shaped upper level, was still bordered by the grape-stake fence. This courtyard acted as the most intimate part of the setting. Conceived in the manner of a Japanese rock garden, a Connell wish that included sand hand-raked by Arthur Connell, the garden also implemented the “nature near” quality Neutra desired. (9) While the original plan called for a solid wall on the east, enclosing the garden, budgetary constraints forced the Connells to erect wood fencing, necessary to keep the deer out, they wrote Neutra. (10)

Mature juniper bushes and large boulders, characteristic of Neutra’s settings, were also present. He consistently employed boulders as devices to contrast the smooth machined finishes of the industrialized world with the rough textures found in nature. Boulders were features of residences such as the Tremaine and Kaufmann villas and small speculative dwellings such as the Hailey House, Los Angeles, 1959 as well as present in public buildings such as the former Garden Grove Community Church, Garden Grove, 1962 (now the Arboretum), and the Orange County Courthouse, Santa Ana, 1968. The extant staggered zig-zag entrance was a Neutra feature intended to decelerate a visitor’s approach to the house, here exaggerated to six quarter-turns.(11)

Richard J. Neutra

Born in

Vienna, Austria, Richard Joseph Neutra (1892-1970) graduated

summa cum laude from the Technical Institute (University),

Vienna. He also attended the informal school founded in 1912

by the radical writer and architect Adolf Loos before

serving with the Austro-Hungarian Empire forces in World War

I. Like his early friend and colleague Rudolf M. Schindler,

Neutra was deeply influenced by the 1910-1911 European

publication of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Wasmuth Portfolios, a

watershed manifesto in twentieth-century architectural

history. The publication illuminated Wright’s radical

conception of the “breaking of the [conventional] box”

through more open plans and an emphasis on the extended low

horizontal line. Both younger architects absorbed and

reinterpreted Wright’s strategies, whose uninterrupted

diagonal sightlines into nature were afforded by long banks

of windows and corner windows. Such configurations became

common in the work of many of the European Modernists and

later in the architecture of the “SecondGeneration”

Modernist architects of Southern California.

Loos, another primary influence, advocated a return to the qualities of humility, anonymity, and what he termed “lastingness,” or durability, in building. Rejecting historicism, Loos argued for a sober, forthright architecture that rejected stylish innovations. These views anchored Neutra’s belief that great architecture did not have to be a series of novel designs hut could evolve detail by detail. In addition, because he established predictable methods, construction costs decreased and allowed the architect to focus on site and user needs.

Despite, his broad education, because of the economy and

lack of opportunities at the end of World War I, Neutra’s

first job was assisting the Swiss landscape architect,

botanist, and gardener Gustav Ammann. Ammann, now considered

an important figure in modern European landscape theory,

promoted the role of nature and landscape as a necessary

component in any architectural setting. Neutra’s early

income in Germany relied on small garden and landscape work.

In these early designs, he specified plant types, budgets,

and maintenance schedules. Beginning in the 1930s, Neutra

typically used more general instructions on the height of

plant or tree, scale of foliage, and plant placement. Later

in his career, Neutra worked with important landscape

architects such as Garrett Eckbo and Roberto Burle Marx, in

which their designs, incorporating curves and other

geometries, offset Neutra’s orthogonal forms.

Neutra

immigrated to America in 1923. He was hired as a draftsman

by the large Chicago firm, Holabird and Roche, where he

mastered steel skyscraper framing and later met another

hero, architect, and critic Louis Sullivan. Beginning in the

fall of 1924, Neutra worked for Wright in his atelier

Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, before moving in early

1925 to Los Angeles, where his fellow Austrian, Schindler,

was based. The city became Neutra’s permanent home. He

worked for Wright before teaming up with Schindler, who,

with Neutra, was responsible for introducing European

Modernism to the West Coast. Apart from his European and

American influences, Neutra’s round-the-world tour in 1930

included Japan. The visit was partially facilitated by the

Japanese architects he met at Taliesin. Neutra’s stay there

was a turning point, as he later wrote in the foreword to a

book on Japanese gardens. The well-proportioned use of

asymmetry and the consistent use of a standard palette of

materials for a wide range of users that he witnessed there

confirmed his belief in his own approach. Additionally, the

fundamental integration of gardens, texture, landscape,

views, and architecture that he admired in Japan

strengthened his conviction that nature or nature’s

qualities were indispensable in architecture. (29)

Neutra’s renown in residential architecture rests on his

command of proportion and his skillful synthesis of

overlapping lines and planes of stucco, steel, and glass

that extend into the surrounding landscape. The Lovell

Health House, Los Angeles, 1929, established his

international fame. Set high in the Hollywood Hills, the

house was a superb expression of the International Style and

the first entirely steel frame residence constructed in the

United States. When he could find no general contractor

willing to take on such a radical project, harnessing his

early experience in Chicago, Neutra himself took on the

challenging project, proving his expertise in innovative

methods in construction. Seven years later in the catalogue

to the landmark 1932 “Modern Architecture” exhibition at the

Museum of Modern Art in New York City, Neutra was hailed as

“the leading modern architect of the West Coast.” (30)

Although chiefly associated with Southern California, he

began working in the San Francisco Bay Area as early as

1935, building a clapboard house on Twin Peaks. Two years

later he designed the boxy redwood-clad Darling house on

Woodland Avenue in San Francisco, which adapted the

minimalist architectural aesthetic of 1920s and 1930s Europe

to regional conditions, placing it within the woodsy

anti-urban Bay Area Tradition.

Neutra

went on to design approximately 400 projects, including

tract developments, National Park Service visitor centers,

churches, colleges, schools, public buildings, defense

housing, and villas in Germany, Italy, and Switzerland.

Although some have been destroyed, especially those on

exceptional sites, a number of properties are now designated

historic resources in the United States as well as protected

internationally, including the early 1960s Bewobau Housing

Development in Germany, and the former U.S. Embassy,

Karachi, Pakistan, 1960, designed with his partner in large

civic ventures, Robert E. Alexander, and declared a historic

monument. Although primarily known for his houses, Neutra’s

achievements range from innovative construction techniques

to his radical reconceptualization of American schools with

strategies that became permanent hallmarks in educational

settings here and abroad. Winner of numerous honorary

doctorates and prizes, he earned the American Institute of

Architects’ Gold Medal posthumously in 1977.

Neutra

grounded his architecture on his immersion in readings in

emerging nineteenth- and new twentieth-century disciplines,

including evolutionary biology, medicine, Gestalt

aesthetics, and other sciences. Collectively, his readings

and personal acquaintance with many of the authors of the

works he read convinced Neutra that an alert contact with

nature, or the qualities of nature, were critical to any

successful human setting. His knowledge of the body’s

physical, sensory, and cognitive systems underscored his

emphasis on creating environments—the building and its

immediate and larger setting— that engaged the senses,

Neutra set forth his theory in his 1954 book, Survival

Through Design.

Additionally, Neutra used his knowledge of Gestalt

aesthetics, refined during his winter teaching tenure at the

Bauhaus in 1930, to “stretch space.” Devices such as

extended balconies, mirrors, and transparent glass,

facilitated such “stretching,” altering the perception of

space to create a feeling of expansiveness. Neutra put these

tools to use in the designs of small houses and

Modern Architecture in Pebble Beach

v

v

Although the history of modern architecture in Pebble Beach

and adjoining communities on and about the Monterey

Peninsula has yet to be written, a broad outline can be

traced with some confidence. In 1933 the distinguished

Modern architect William Wurster, dean of the University of

California, Berkeley, from 1950 to 1963 and one of the

principal figures associated with the Bay Area Tradition,

designed a Carmel house for E. C. Converse. The abstract

design reinterpreted features of the then popular Colonial

Revival style, for which Wurster received an Honor Award

from the northern California Chapter of the American

Institute of Architects. Far removed from the hard-edge

International Style associated with Neutra and its

reinterpretation by his countryman Rudolph Schindler, the

Converse house nonetheless embodied a new architectural

sensibility associated with the Bay Area, a “gentle

modernism,” to use the evocative phrase of the architectural

historian David Gebhard. (31)

Other

expressions of this design outlook arose in Carmel prior to

World War II, including the Sand and Sea complex, comprising

five houses and a garage with a studio above, at the corner

of San Antonio Avenue and 4th Street. This development was

the work of Jon Konigshofer, a prominent Carmel designer and

builder who played a large role in bringing West Coast

regionalism and the Bay Area Tradition to his adopted

hometown and the surrounding area. His design was a handsome

example of “everyday modernism,” interpreted as that

mediation between the stark rationalism of the International

Style and the regional climate, conditions, and concerns

that animated the architecture of other figures associated

with the Bay Area Tradition who worked in and about the

Monterey Peninsula, including Gardner Dailey, Henry Hill,

and Clarence Tantau Within this context, it should be noted

that in 1939 Neutra himself produced a handsome redwood-clad

house for William and Alice Davey (now significantly

altered) on Jacks Peak, outside Monterey, that was

thoughtfully integrated into the surrounding landscape of

grassland and Monterey pines.

In

contrast to Carmel and Monterey, Pebble Beach did not see

the introduction of Modernism until some years after World

War II, though the lack of a comprehensive local

architectural history, together with the difficulty of

viewing many of the community’s residences from public

thoroughfares, makes a definitive assertion on this point

impossible. (32) In 1940 Frank Lloyd Wright designed a

spacious house for John Nesbitt on 17 Mile Drive, but it was

never constructed. Seven or eight years later Jon

Konigsberger designed a notable Modern residence for the

Robert Buckner family in Pebble Beach, which was one of

fifty-three houses featured in the 1949 San Francisco Museum

of Art exhibition, “Domestic Architecture of the San

Francisco Bay Region.” In 1952 he designed a Modern house

for Macdonald and Margaret Booze on Signal Hill Road, just

down the street from where Neutra would build. Throughout

the mid-century a significant number of other architects

associated with Mid-Century Modernism produced handsome

homes in Pebble Beach. Within this context, the Connell

House is clearly significant as an extremely important

example of residential design, exemplifying both the

rational approach associated with Modern architecture

generally and the character-defining features associated

with the International Style specifically.

Richard

Neutra’s hundreds of award-winning properties are primarily

found in Southern California. As an accomplished and rare

example of the work of this master architect in northern

California, with a superb setting in which Neutra could

fully realize his beliefs about human well-being, the

Connell House is unequivocally an important example of the

International Style, perfectly illustrating this design

aesthetic within the context of the development of Modern

architecture in Pebble Beach.

31

David Gebhard, “William Wurster and His California

Contemporaries: The Idea of Regionalism and Soft Modernism,”

in Marc Treib, ed., An Everyday Modernism: The Houses of

William Wurster (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of

Modern Art; and Berkeley: University of California Press,

1995), 169.

32 The

relatively late appearance of Modernist architecture in

Pebble Beach can be traced to the building restrictions Del

Monte Properties Company introduced into its real estate

deeds in the 1920s. The restrictions, as the company took

pains to explain to prospective purchasers, were intended to

create communities “harmonious within themselves” and to

“prevent the erection of undesirable and unharmonious

buildings that would depreciate those of their neighbors.”

The type of residential design Del Monte Properties believed

“best suited” to the area was founded on the traditions”

brought to California “by the first Spanish settlers. It has

the general characteristics of the architecture of those

countries along the north shores of the Mediterranean from

Gibralter [sic] to the Dardanelles, where the climate and

topography are so similar to ours.” Although the

restrictions were relaxed as the Depression wore on, as late

as 1940 Fortune magazine, reported that when submitting

architectural plans for approval, “it will be better, no

matter what the size of your purse, if you plan a

Spanish-Colonial (Monterey) type of house.” Del Monte

Properties Company, Bulletin, December 1, 1927, Pebble Beach

Company Archives, Pebble Beach; “Del Monte,” Fortune 21

(January 1940): 106.

Additional Photos

Sources

Blanton, John. Telephone interviews with Barbara Lamprecht. December 18 and 23, 2013.

Connell, Alexandra. Telephone interview with Barbara Lamprecht. January 3, 2013.

“Del Monte.” Fortune 21 (January 1940): 56-67.

Del Monte Properties Company. Bulletin, December 1,1927. Pebble Beach Company Archives, Pebble Beach.

Dodson, Denise, et al.

Architecture of the Monterey Peninsula. Monterey: Monterey Peninsula Museum of Art,

1976.

Engel, David. Japanese Gardens

for Today. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle, 1959.

Gebhard, David. “William Wurster and His California Contemporaries: The Idea of Regionalism and Soft Modernism.” In An Everyday Modernism: The Houses of William Wurster, edited by Marc Treib, 164-183. San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Hines, Thomas S. Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture. 4th ed. New York: Rizzoli International Press, 2005.

Hitchcock, Henry-Russell and Johnson, Philip. The International Style: Architecture Since 1922. New York: Museum of Modern Art Press, 1932.

Lamprecht, Barbara. “Neutra in Japan, 1930, to His European Audience and Southern California Work.” Southern California Quarterly 92 (Fall 2010): 215-42.

Neutra: Selected Projects. Köln: Taschen, 2004.

Richard Neutra—Complete Works. Köln: Taschen, 2000.

Kirk, Anthony, and Barbara Lamprecht. Arthur and Kathleen Connell House, 1170 Signal Hill Road, Pebble Beach/Del Monte Forest, Monterey County, California, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. January 15, 2014.

Mandros, Miltiades. Survey, northern California Neutra properties. Barbara Lamprecht Collection.

Neutra, Richard J. Life and Shape. Los Angeles: Antara Press, (1962) 2009.

Mystery and Realities of the Site. Scarsdale, New York: Morgan & Morgan, 1951.

Nature Near: The Late Essays of Richard Neutra. Santa Barbara: Capra Press, 1989.

Survival Through Design. New York: Oxford University Press, 1954.

World and Dwelling. Stuttgart: Verlanganstalt Alexander Koch, GmBH, 1962.

Neutra, Richard and Dion. Pflanzen, Wasser, Steine, Licht. Berlin: Verlag Paul Parey, 1974.

Page and Turnbull. Pebble Beach Historic Context Statement. San Francisco: Page and Turnbull, August 29, 2013.

Roland-Nawi, Carol. California State Historic Preservation Officer. Letter to Craig Spencer, Associate Planner, County of Monterey, RE: Connell Arthur and

Kathleen House, Determination of Eligibility, National Register of Historic Places. July 11, 2014.

SWCA Environmental Consultants. “Signal Hill LLC Combined Development Permit, Final Environmental Impact Report.” Prepared for County of

Monterey Housing and Community Development. October 2022. SCH No. 2015021054.

University of California, Los Angeles. Charles E. Young Research Library, Department of Special Collections, Richard and Dion Papers, Collection 1179.

Woodbridge, Sally, ed. Bay Area Houses. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.